A Colombian fisherman vanished after US forces bombed a boat in the Caribbean. Now his family is pursuing legal action that could implicate a Canadian arms manufacturer whose targeting cameras guided the strike.

Author: Bruno Sgarzini

“I’m going fishing, I’m going to be out of communication,” said Colombian fisherman Alejandro Carranza before heading out to sea in his small motorboat on 14 September. Neither his daughter Zaira nor he knew those would be his last words before disappearing for two months without a trace in the Caribbean, a territory described by writer Juan Bosch as “an imperial frontier” due to constant disputes between European powers during colonial times.

Both Zaira and her mother Katherin believe Carranza’s disappearance has an explanation: the US bombing on 15 September 15 of a boat with two motors, similar to his, in the waters off La Guajira, Colombia. At school, his son Livinston’s classmates often ask if the person in the video is his father. “He asks me why they didn’t arrest him instead of killing him. And I stay silent, because I don’t know how to respond,” his mother says. The Carranzas, a humble Colombian fishing family, are now seeking to prosecute those responsible for the bombing in the United States with support from American attorney Dan Kovalik.

But the trail of responsibility is much larger and includes a Canadian subsidiary of arms manufacturer L3Harris Technologies. Carranza’s boat was bombed with the use of a sensor camera manufactured by Wescam, a division of the Ontario-based arms company frequently used to guide attacks or monitor “targets” before bombing, according to a Project Ploughshares report.

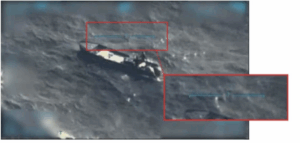

Kelsey Gallagher, author of “Attacked from Above: Canadian Sensors Enable Illegal U.S. Airstrikes in the Caribbean”, determined that an MX-Series camera, manufactured by L3Harris Technologies Wescam, was used in the 2 and 15 September attacks based on White House images. The footage shows clear aspects of the interface used by the manufacturer, with text, symbols, and on-screen reticles visible in the sensor transmission. “Despite having deleted several parts of the video, one distinctive feature remained visible: a light blue scale bar used to measure the size and distance of visible objects, a characteristic element of WESCAM’s MX-Series sensor interface.”

L3Harris Wescam, based in Hamilton, Ontario, is one of the world’s leading producers of electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors. Its MX Series system, used by militaries and law enforcement for real-time surveillance and target tracking, has been sold to the US Department of Defense. Currently, the company has a $380 million contract to provide these cameras to the US Army, managed by the Canadian Commercial Corporation. “WESCAM has supplied its EO/IR sensor suite to the US military for over 25 years,” according to Project Ploughshares.

Screenshot of the attack on the boat believed to belong to Colombian fisherman Alejandro Carranza, made by Project Ploughshares.

This isn’t the first case where Canada and L3Harris Wescam have been questioned over camera use in human rights abuses. In October 2020, Canada banned their shipment to Turkey after revelation they were used in Bayraktar TB2 drones to attack civilians and carry out extrajudicial executions in Syria, Libya, and the former republic of Artsakh, invaded and occupied by Azerbaijan. Canadian authorities applied the UN Arms Trade Treaty terms, which obligates signatories to ensure arms sales “do not contribute to serious violations of international law, including violations of international human rights law.” Canada could do the same with Wescam camera shipments to the United States. However, the main obstacle is the Defense Production Sharing Agreement with the US, signed in 1959, which exempts most Canadian military exports to the US from requiring export permits.

The US bombings in the Caribbean have been questioned due to the flimsy legal theory put forward by the Trump administration for the argument: the president assumes war powers in the context of “an armed conflict” against drug cartels that kill Americans with their drugs, according to The New York Times. However, for Juanita Goebertus, director for Latin America at Human Rights Watch, “there is no armed conflict between the United States and Venezuela, or between the United States and Colombia, or between the United States and these common crime groups. What exists is an organized crime phenomenon that must be confronted by law enforcement officials who investigate, prosecute, and sanction drug trafficking networks, but do not summarily execute suspects on vessels in the Caribbean and Pacific.”

“The use of lethal force in international waters without adequate legal basis violates international law of the sea and amounts to extrajudicial executions”, according to several UN rapporteurs. For Tulio Alberto Álvarez-Ramos, head of the Constitutional Law Department at the Central University of Venezuela, victims’ families, such as Carranza’s, could bring their case to US courts citing the Alien Tort Statute, which allows foreigners to sue the United States for violations of international law. The problem is that those killed are considered by the Trump administration as “foreign enemies for belonging to drug cartels,” according to various executive orders.

But the story could be different regarding sensor cameras manufactured in Canada. Sujith Xavier, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law at the University of Windsor specializing in public international law and Canadian public law, argues that there could be legal consequences for executives and the manufacturing company, L3Harris Technologies Wescam, if the US attacks are found to constitute war crimes. Canada has adhered to conventions against war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, such as the Geneva Convention, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. “These prohibitions are now part of Canadian legal order since the enactment of the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act of 2000 and amendments to the Canadian Criminal Code,” says Xavier. “The use of Canadian technology could be understood as aiding and abetting these crimes, which is prohibited under Canadian law”.

The MX Series camera line from L3Harris Technologies Wescam can be carried on Reaper drones or Poseidon 8 aircraft, among others deployed by the United States in the Caribbean.

According to Xavier, there are precedents where this law was used against people who committed atrocities in the Rwandan genocide and the Congo war. One example was Désiré Munyaneza, leader of an Interahamwe militia responsible for massacres in Rwanda, convicted of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Munyaneza was the first person convicted of crimes committed in a third country after seeking refuge in Canada. “So there is a possibility that the Canadian company could be held responsible, even though there are only precedents against individuals,” according to Xavier.

There are international precedents where companies were convicted of crimes against humanity, such as companies in Nazi Germany. Additionally, in Canada there is the Nevsun case, in which three Eritrean workers at the Bisha Mining Share Company mine, a subsidiary of Canadian company Nevsun, initiated legal action for having been enslaved, forced to perform 60-hour weekly forced labor, and tortured. The Supreme Court of Canada rejected the company’s appeals demanding the case be tried in Eritrea, arguing that Nevsun had violated customary international law, which establishes penalties against slavery and forced labor, recognized as part of Canadian legal order.

This precedent allows other Canadian multinationals to be held responsible if proven they committed violations of customary international law in other countries, according to Andrés Denny, director of the Public Law Group in the United Kingdom.

This becomes quite relevant considering Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s statements about bringing legal action in the United States for the alleged murder of Colombian fisherman Alejandro Carranza and two other men from Trinidad and Tobago, whose families reported the possibility they were hit by US bombs. For Xavier, Colombia would have several legal avenues: “If their lawyers represent a family member of someone who died in one of these attacks, they could sue the company and the Canadian state in the country’s courts under charges contemplated in the war crimes law. Or ask the Canadian government to investigate these events through the attorney general. A class action lawsuit for damages could also be initiated, as was done, unsuccessfully, by a group of Palestinian villagers against a company for building an apartheid wall in 2009.”

Another possibility could be filing a lawsuit against Canada in the International Court of Justice for aiding and abetting war crimes through the use of technology. The same could be done in the International Criminal Court, since both Ottawa and Bogotá are signatories to the Rome Statute. One of the biggest obstacles is that most of those killed remain missing in Caribbean waters; the evidentiary burden of any case — the vessels, the cargo, the bodies — has been destroyed by the bombings, as is the case with Colombian fisherman Alejandro Carranza, whose humble family could face off in Canadian courts against the powerful lawyers of L3Harris, owned by BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Corporation. A true David versus Goliath.